Appendix 4: “I Could Be Catholic If It Weren’t For…”

I have heard this almost as many times as I said it myself. For a Protestant, there are a lot of doctrines in Catholicism that just seem weird. No contraception? Praying to saints? Some old man in Rome tells me things about Jesus and I just have to believe him? I’m required to accept that Mary was both preserved from sin and remained a lifelong virgin? It feels like being asked to carry an enormous backpack stuffed with strange objects of crushing weight. It’s overwhelming, disorienting, and frustrating. Things get a lot worse if there is not a knowledgeable, winsome Catholic nearby to answer questions well (a problem my friends will be spared). The “Catholic but” crowd has my full sympathy. Yet I cannot help feeling that they are being inconsistent.

A very quick primer on recent Catholic history. In the 1860’s, the Catholic Church held an ecumenical council, which just means that the pope gathered a host of high-ranking clergy to deliberate on some important matter pertaining to the Faith. One upshot of the council was the ruling that the pope has unilateral authority to define Christian doctrine under certain circumstances. Some statements the pope can issue are infallible, cannot possibly err. This has only been officially used for two doctrines: the Immaculate Conception and the Bodily Assumption of Mary. These say that Mary was miraculously conceived without sin and preserved from it by God for her whole life, and that at the end of her life she was brought bodily into heaven like Enoch and Elijah.

This, of course, is a very hard pill to swallow for Protestants. In fact, it is the number one doctrine cited in a “Catholic but” statement. Everything seems to make sense, but then you go ahead and add that Mary was sinless and, by the way, if I don’t submit to that I can’t be Catholic? This council, known as Vatican I, makes it very hard for Protestants to think of Catholicism as the fulfillment of Christianity rather than a bizarrely twisted aberration.

Enter Vatican II. In the 1970’s, there was another council. This one is still far from making its full effects felt, but it had two relevant upshots. The first was a dramatic reform of the liturgy. Suddenly Mass didn’t always have to be in Latin—it could be in the peoples’ native tongues. Priests no longer faced Eastward, but toward the congregation. Protestants were seen much more positively, and some were even invited to be official observers of the proceedings. Non-Catholic Christians were referred to not as “schismatic heretics” (although that remains true, in a sense), but “separated brethren,” with the continued reminder that reconciliation is essential to the Church’s mission. In these and many other ways, Vatican II represents the final victory of Protestantism. Or at least of Luther. The reforms demanded by the original leading lights of the Reformation were finally delivered. This observation came to me from an essay by prominent Protestant theologian Stanley Hauerwas, in which he raises the question: If the Catholic Church has successfully been reformed, why are we still Protesting? His answer is halfhearted and totally unconvincing. The best he can say is that, well, his wife is an Episcopal priest, which would make things awkward.

Vatican II makes it possible for serious Protestants to consider Catholicism. Vatican I makes it difficult. Thus “Catholic but”. The continuity, and perhaps even superiority, of Catholicism viz a viz Protestantism is clearer now than it ever has been. But that very similarity makes the Catholic distinctives seem all the stranger. It’s a theological uncanny valley. Yet the walls are not so steep as to leave us trapped.

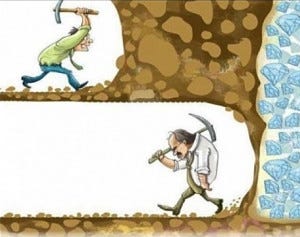

In my 18-month struggle with Catholicism, I looked for a reason, any reason at all, to stay Protestant in good conscience. At times it seemed I had found something to grab hold of that would arrest my slide, the kinds of things Protestants always Protest against, the kinds of things I named above. But a second thought would always come close on the heels of the first, with all the horrible inevitability of good logic. The following statements do not seem to go together:

The Catholic Church has gotten (nearly) everything right for two millenia.

No other church has been able to avoid schism while continuing to develop and define doctrine. (Protestants fail the first, Eastern Orthodox the second.)

But there’s this one specific doctrine or handful of doctrines I just can’t get behind.

Therefore, the claim of the Catholic Church to authoritatively interpret the Christian Faith is invalid.

Once you have (1) and (2) on the table, it is hard to see how you get from (3) to (4). It seems like what you should do is conclude from (1) and (2) that, even if (3) you cannot see how a particular doctrine could be true or could be derived from Scripture, you should (4*) submit to the Church’s authority and accept it, even if you don’t yet fully believe it.

This is an important distinction to make. The facts we assent to are largely out of our voluntary control. If it just doesn’t seem like Jesus rose from the dead (no matter what your reasons tell you), we may not be able to drum up belief by sheer willpower. That would be mere wishful thinking. But what we can do is assent to the doctrine, take it as true for our lives and act in hopeful prayer that God (whom you may or may not find yourself believing in yet) would grant you the grace to come to full belief. Submission to a king’s authority does not require that you like or agree with all his laws. Or, to some extent, that you even find it easy to believe in him. What counts is whether you follow his word.

If you “would be Catholic but,” I offer you the following challenge. Historically, trusting the Church’s teaching has enabled lay Christians to tread orthodoxy’s narrow ridge with confidence, often hardly aware of heresy’s gaping abyss just inches from the path. Millions upon millions of people have implicitly or explicitly held firmly to formulas that take years of scholarly study to fully understand. Yet the masses do understand them, and many are even willing to die confessing them. What would have happened if the Protestant preference for private judgment had been in Christianity’s DNA at the beginning? There would now be no Faith to inherit. To even make the “Catholic but” argument is already to draw upon the massive strength of the Catholic Church’s ability to preserve true doctrine for her children. And to acknowledge this is just to admit that she has been God’s chosen instrument for guarding, unfolding, and promulgating the Gospel message.