Essentials-Based Unity Rips the Church Apart

Or, How a Heretical Archbishop Shaped Modern Protestant Ecclesiology

In necessariis unitas, in dubiis libertas, in omnibus caritas

“In the essentials, unity. In non-essentials, freedom. In all things, charity.”

Little has done more to damage Christian unity in the last hundred years than this sentiment. Even the history of the quotation reflects this. It is usually misattributed to St. Augustine, but in reality comes from a 17th-century anti-Catholic polemic. If you don’t believe me, here is the immediate context:

But if at the very root, that is, the seat, or rather the throne of the Roman pontiff, this evil of abomination were purged and, by the common counsel and consent of the church, this fear was removed; most splendid. And let us all embrace one another, in necessary things unity; in uncertain things liberty; in all things charity. I feel so, I wish so, I hope so plainly, in him who is our hope and we shall not be disappointed. I feel so, I wish so, I hope so plainly, in him who is our hope and we shall not be disappointed.

That last repetition is not a typo. It is as if the absurdly interesting heretical archbishop who penned it, Marco Antonio de Dominis, is pleading with us, or rather himself, adjuring himself to believe that God will in fact work how de Dominis feels, wishes, and plainly hopes He will.1 But will He? There are exceptionally good reasons to think not.

First, Scripture nowhere indicates a list of the “essentials.” There are plenty of summaries of the Gospel, plenty of pithy phrases meant to capture key elements of Christian teaching. But none of them is marked off by an introduction that says something like, “Hello all you Galatians. There’s been a lot of disputes recently over minor details, like all this circumcision stuff. So before I give you my take, let me just lay out what makes for a salvation issue.” Not only is there nothing like this explicit marker in Scripture, there’s nothing that generally corresponds to concepts like “salvation issue,” “primary doctrine,” or “the essentials.” Paul never shies away from using his teaching authority to weigh in on something because its a “peripheral” question. Consider his somewhat esoteric reflection on the nature of our resurrected bodies:

But someone will ask, “How are the dead raised? With what kind of body will they come?” How foolish! What you sow does not come to life unless it dies. When you sow, you do not plant the body that will be, but just a seed, perhaps of wheat or of something else. But God gives it a body as he has determined, and to each kind of seed he gives its own body. Not all flesh is the same: People have one kind of flesh, animals have another, birds another and fish another. There are also heavenly bodies and there are earthly bodies; but the splendor of the heavenly bodies is one kind, and the splendor of the earthly bodies is another. The sun has one kind of splendor, the moon another and the stars another; and star differs from star in splendor.

So will it be with the resurrection of the dead. The body that is sown is perishable, it is raised imperishable; it is sown in dishonor, it is raised in glory; it is sown in weakness, it is raised in power; it is sown a natural body, it is raised a spiritual body.

I’m sure a lot is going on here, some of which I have guesses about. But notice Paul’s first reaction: “How foolish!” You might expect, on the de Dominis paradigm, that his next sentence would be, “Why waste time speculating about these distant things? Trust God and love others!” Paul’s real answer reveals just how far from de Dominis the New Testament is. Paul uses his teaching authority as a bishop (Greek episcope, “overseer”) to weigh in on a theological matter that would today fall far outside what essentials-based unity permits. I could adduce dozens, possibly hundreds of examples of this, including teachings on wealth, sexual ethics, qualifications for ministry, that odd detail about the naked guy in Mark, the entire book of Revelation, etc. It’s exactly as if the New Testament has no idea that it ought to clearly distinguish between which parts of the Gospel we’re obliged to accept and which we can demur on.

But wait, maybe I’m being too hasty. All those secondary issues (pace the fact that this term appears nowhere in Scripture) matter, but perhaps they just matter less than the ones we absolutely must agree on to have anything worth calling assent to the Christian Faith. This reply is an almost irresistible salve to the anguish of the shattered state of Christianity in the West. Consider, though, what it implicitly says back to the Bible: “Well, I can see you’re saying something here, but it’s just not clear. And, in any case, it doesn’t seem like whether I accept it disturbs the core tenets of Christian teaching, so I’m going to just play it safe and ignore this passage.” This is not a caricature. A recent conversation with one of my former professors, whom I respect more than almost anyone else, offered a depressingly vivid illustration of this attitude.

His church had been deliberating about whether or not to publicly declare that same-sex unions can be marriages,2 and the conclusion they came to used the following logic:

Scripture is not outright against same-sex marriage, because the concept of two same-sex persons of equal standing in a permanent relationship of love would not have been available to the authors of the New Testament. (The historical bit of this premise, at least, is reasonable.)

What Scripture does say seems to lean in the direction of a traditional (read: orthodox) understanding of marriage.

But while the penalty for removing a command from the Law is being “least in the kingdom” (Mat. 5:19), causing “one of these little ones” to stumble on their way to Jesus is worse than being tossed into the ocean with concrete shoes (Mat. 18:6).

Thus, because Scripture isn’t overwhelmingly clear, and the penalty for being morally lax is lesser than the penalty for preventing someone from coming to Christ, we ought to err on the side of caution and loosen our definition of marriage so no one feels blocked from Christ.

Make of the argument what you will. Love it or hate it, it’s hard to see how essentials-based Christianity was ever going to avoid this kind of probabilistic reasoning. The de Dominis paradigm waives off difficult biblical passages like so many flies.

The approach is unbiblical twice over, because not only does the theology of the New Testament militate against it, but the narratives do as well. Although memoralist Protestants frequently marshall the Thief on the Cross as evidence that Baptism doesn’t save, they do not follow up with a reasonable way to explain what does save. In fact, it is devastating for an essentials-based vision of unity. The Good Thief, whom tradition names Dismus, is the only person to be canonized by Christ Himself: “Truly I tell you, this day you will be with me in Paradise.” Here is a brief list of the things Saint Dismus could not have possibly understood:

The hypostatic union

The New Testament

The Trinity

The Gospel

You are free, of course, to make things up. You can say that if Saint Dismus had been presented with these doctrines (presumably not while being crucified), then he would have assented to them. But we can’t know that. And even if we could, it would drag in the somewhat strange implication that people are retrospectively accountable to a deepened understanding of Christian doctrine that takes place centuries after their death.

And there’s more. I may be so bold as to say that essentials-based unity is unbiblical thrice over. Not only is it out of step with the epistles and narratives of the New Testament, but the prayer of Christ Himself. In His “Great High Priestly Prayer,” Jesus prays the following:

“My prayer is not for [my present followers] alone. I pray also for those who will believe in me through their message, that all of them may be one, Father, just as you are in me and I am in you. May they also be in us so that the world may believe that you have sent me.”

This poses a very pointed question to de Dominis and his progeny: Given that “being one” is linked to a shared witness, in what meaningful sense can a church be called “one” if it is divided on so-called secondary issues such as abortion, contraception, pacifism, hell, salvation, forgiveness, sin, Baptism, Communion, church leadership, and more?

The case against de Dominis gets worse still. As I hinted above, the essentials-based vision of unity is deeply linked to soteriology, doctrine concerning salvation. The assumption is that primary issues are those that can only be dissented from on pain of eternal damnation. If that’s so, then it becomes infinitely important to get this right. The lack of a clear list, at this point, becomes unbearably alarming. More so when you find out that the leading Protestant philosophers today are denying doctrines held with universal assent just a few centuries ago. Alvin Plantinga, in “Does God Have a Nature?” denies divine simplicity, which is a foundational element of all doctrine of God ever held in any Christian tradition. William Lane Craig not only denies divine simplicity but divine timelessness as well,3 and, perhaps even more troubling, dissents from the Sixth Ecumenical Council, which isn’t even the more controversial Seventh Ecumenical Council that Protestants more frequently object to. On the theological side, massively influential theologian Wayne Grudem, whose Systematic Theology was a standard text for entire seminaries, advocates a view that would rewrite the doctrine of the Trinity, Eternal Subordinationism.

One more objection to essentials-based unity, one close to my heart. When there is no authoritative, systematic guidance on what it means to live a life consistent with the Gospel, believers have three options:

Hold opinions whose strength far exceeds their evidence.

Adopt a pragmatic approach like the one outlined above.

Throw in the towel and let Christianity shrink to the size of whatever meager agreement may still be found.

Because Catholic doctrine becomes more defined while Protestant doctrine becomes less so as consensus breaks down, time will exacerbate rather than relieve this awful trilemma. The early Christians show no evidence of thinking that the Faith couldn’t be articulated with confidence beyond a few irreducible mathematical points. They came together certain that Christ had come to extend His reign to the entire world, and they made decisions they took to be binding on every Christian conscience. No one should be sold a Christianity that stutters when it comes time to proclaim what the Gospel reveals for right belief and just living.

A More Excellent Way

Why does Catholic doctrine extend while Protestant doctrine shrinks? Simple: the Magisterium. The teaching authority of the Catholic Church, which resides in its bishops under the earthly headship of the Pope, offers an alternative to the essentials-based view that escapes the dismal picture painted above. The Magisterium has the authority to pronounce definitive rulings on matters of faith and morals, forever blocking what might otherwise be a tempting theological avenue with a great sign like the one Dante found over the entrance to Hell, “ABANDON ALL HOPE, YE WHO ENTER HERE.”4 Far from being motivated by a desire to dominate or extort, the Magisterium exercises the same sort of care that leads a city council to put guardrails up on a corner that’s seen one too many crashes.

Before I outline how this approach works, I need to pause and note an assumption that has been implicit to this point but needs to be examined directly to understand how the Catholic method, which I call the definition paradigm, works. Throughout, I have equated ecclesiology with soteriology. That is, I started with a premise about essentials-based unity, then proceeded to talk about essentials-based salvation. This is because ecclesiology and soteriology are always connected.5 But that doesn’t mean all ways of relating them are on a par. The de Dominis paradigm defines the “capital-C Church” as the collective body of Christians, so being a member of the “universal Church” is just the same as being saved, which largely consists of assent to the “essentials.” Thus, any time the de Dominis paradigm speaks of Christian unity, it is also talking about salvation, and vice versa.6 It seems to me, however, that we should try to tease these two notions apart.

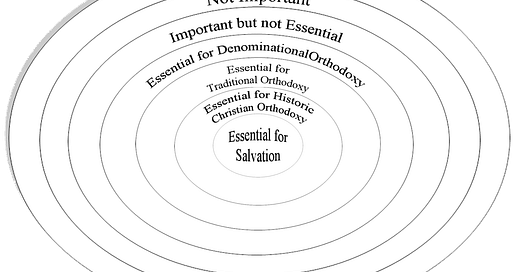

In philosophy, sometimes we talk about the granularity of a proposition: just how much does it contain? For example, “All dogs are good boys” is equivalent in content but not in granularity to an exhaustive list of all dogs each individually declared to be a good boy. When you attend to granularity, you often find much more packed into a proposition than there first seems to be. It’s an instance of the Expanding Coastline Paradox: if you ignore all bays and inlets, you will have an initial measurement of the coast’s length, but you can get more and more detailed, following every curve and harbor—eventually every grain of sand and atom of silicon. With each added level of detail, the total miles of the coastline increase, and there is no non-arbitrary point to say, “Ok, this is enough detail, stop here.” Doctrine develops the way coastlines expand. Not by changing, and not by the addition of new material, but by a deepened understanding of what is contained in the original proposition.

As we increase in granularity, “Jesus is Lord,” turns out to contain “Jesus is fully God,” and “Jesus is fully man.” These, too, contain further propositions. “Jesus is man” turns out not to mean that Jesus merely seemed to have a human nature (a heresy known as “docetism,” from the Greek dokein, “to seem”) but really had a full, complete human nature. “Jesus is fully God” means that He did not merely have a nature “just like” God’s, but that He shared the very same nature as the Father. Although all proponents of an essentials-based view would readily agree that these examples are genuinely contained in the original “Jesus is Lord,” it was not always clear. Coming into the First Ecumenical Council at Nicea in 325 AD, it may even have been that a majority of Christians were Arians, meaning they believed that Christ was a creation of the Father and not God Himself. They had the same Bible we7 do. Yet what seems plainly obvious to us was not so to them. What happened in the interval? It wasn’t a Josiah-like discovery of a verse from John or Paul that the Arians forgot about in a fit of mass amnesia. It was the definitive ruling of the Church at Nicea, the enforcement of which was aided by sympathetic Roman emperors. It is simply an empirical fact that it has been far, far from obvious to every serious Christian what all is contained in the initial proposition, “Jesus is Lord.” The essentials-based view is indebted to thousands of years of the Magisterium exercising its teaching authority.

Now we are in a position to make sense of the definition paradigm. On this view, the one held by the Catholic Church, you are accountable to whatever you can reasonably be held accountable, and the Magisterium of the Catholic Church has the power to define (that is to say, definitively rule on) doctrine. Because the Magisterium has unlimited authority to delimit what is and is not contained in the expanding coastline of Christian doctrine, all who know the truth about the Catholic Church are obliged, on pain of eternal damnation, to submit to her decrees. It may sound harsh, but it is a logically airtight deduction:

The Catholic Church has the authority to define what is (and is not) contained in the Gospel.

The Catholic Church teaches that x is contained in the Gospel.

x is contained in the Gospel. From 1, 2

Therefore, to knowingly reject x is to knowingly reject an element of the Gospel. From 3.8

Everyone in the “nonculpably nonCatholic” category would object to Premise 1. But the moment they come to recognize the truth of the Catholic Church’s claims about herself they become accountable to everything they know she teaches. Until then, while they still reject Premise 1, they might come to know Premise 3 on other grounds. Say, for example, someone is convinced that the logical outworking of “Jesus is Lord” contains both “Jesus is God” and “Jesus is man.” This knowledge now fills in “x” in Premise 3. Because they know Premise 3, they become accountable to it by Premise 4. But it will be an unreliable accountability, since what appears to be a stronger argument might come along tomorrow and undercut their reasons for believing Premise 3.

As time goes on, controversy arises over what is contained in the Gospel. It has been this way from the beginning, it will be until the end. Through it all, the Magisterium definitively answers, forever binding the conscience of all who stand in her shade. This means that while the Protestant, essentials-based approach will lose more and more ground over time as it is unable to systematically and finally settle debates, the Catholic Church will continue to extend the reign of Christ over all things. If Christianity is true, then the Triune, Incarnate God is at the center of all things. All things are from Him, by Him, and to Him. How could it be otherwise? The definition paradigm sees the Church not as the guardian of some small set of truths whose contents and implications for the rest of reality cannot be confidently determined, but “terrible as an army with banners,” marching ever onward to put all things under Christ’s feet. In light of this high calling, it would be foolish to think that you could reduce everything meaningfully revealed by the Gospel to a few punchy sentences, or something like an “Eight Essentials” rubric for church membership. Of course, punchy sentences have their place and, not to be outdone by a long-dead heretic, I’d like to offer my own:

In definitiis unitas, in indefinitiis libertas, in omnibus caritas

I don’t know Latin, so someone can write in to tell me if that’s actually how it would be written. I’m more confident in the English translation:

“In things defined, unity. In things undefined, liberty. In all things, charity.” 9

Where does this leave Protestants? Are they different only in degree from Mormons, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and other groups we all agree sit outside the Christian fold? Yes, and no. Yes, they are different in degree: both Protestants and true apostates object to teachings ultimately contained in the Gospel. But no, they are not different only in degree. Different points along the “dissents from the full truth” spectrum have different statuses. The edge of Christianity, by my lights, runs along the question “Does this group have valid Baptism?”10 I could not possibly begin to unpack the theology of Baptism here, but the teaching of the New Testament is that it is the ordinary means whereby someone dies to self and becomes alive to Christ, joined implicitly to the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church even if the person does not recognize it or enter into full communion. Another important division in the spectrum comes at the question, “Do they have Apostolic Succession?” If the answer is “Yes,” then they enjoy all seven sacraments.11 Remember, though, that “Where on the dissent spectrum does someone fall?” is a different question than “Are they saved?” The answer to the second question will depend on whether they submit to what they can reasonably be held accountable to, not simply how much of the truth they know. Recall Saint Dismus. We don’t have to say anything about “the essentials” in his case because all he could reasonably be held accountable to was what he did in fact acknowledge: that Jesus was blameless, that He had some kind of spiritual authority, and, most importantly, a commitment that amounts to “Wherever you go, I want to be.”

You are at this point wondering, I hope, “When can someone “reasonably” be held accountable to something?” We could probably make some general statements here, but the truth is that it is rather murky for us mortals, who see “through a glass darkly.” Rest assured, though, that God will have justice. In the end, no one will be able to rightly complain that they were treated unfairly. Thus if you’re seriously concerned for yourself, there’s only one solution: you must come home. You must yoke yourself to Rome and all she teaches. Christ foresaw the immense chaos and caustic division that would follow from everyone having to sus out Christian teaching individually, or even as a local church. He has taken this burden from us and given us the duty to obey in its place. Do not rush to throw it off, to ease the cognitive dissonance by saying to yourself, “Ah, but I don’t have good reasons to believe the Catholic Church is who she claims to be, so I don’t need to be worried about what I would be accountable to if I did.” You have been given good reasons to suspect the truth. Be careful that you do not go away sorrowing because this unexpected cost of following Christ is too high.

Let us review the argument. The essentials-based view is entirely without scriptural support, and has the sad effect of slowly decaying Christian teaching from a comprehensive vision of life, the universe, and everything, to a handful of sterile sentences from which few, if any, certain deductions can be drawn. Although it initially sounds like a magnanimous approach to intra-Christian disputes, it ends by giving up all the things we originally cared about enough to fight over. A definition paradigm, on the other hand, stems organically from New Testament, correctly sorts the test cases, and casts an expanding rather than shrinking vision of Christian doctrine. It does, however, have some very uncomfortable implications. It means rejecting the addictive numbness that essentials-based unity constantly administers to the open wound of our manifest disunity. But this is a feature, not a bug. We should be scandalized, horrified at the schisms that score the body of Christ like the cruel Roman whip. Because the Church is the Body of Christ, and because our salvation consists of being joined to Him, in the end ecclesiology and soteriology are really Christology. The essentials-based view, as reflected in the life of its progenitor, de Domonis, puts the Church to sunder, and so doing puts Christ to sunder. This is no exaggeration. Remember the words of Our Lord: “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute ME?”

< Saints F.A.Q. | F.A.Q. List | Building It >

The life of de Dominis is instructive and well worth a read. He began excoriating the papacy before being welcomed as a kind of theological propagandist by England. Because his personality could have been the central case study in How to Lose Friends and Influence With People, it was only a matter of time before he would fall out of favor with his host country. He successfully entreated Rome to take him back, and upon arrival declared that everything he’d written previously (including the quote above) had been a lie meant to ultimately show the absolute supremacy of the papacy over temporal rulers. But eventually his pension from the Pope dried up and, to quote this surprisingly gripping Wikipedia entry, “irritation loosened his tongue.” It was only a matter of time before the Inquisition would deem him a relapsed heretic and sentence him to isolation. Since he theologically betrayed both Protestant England and Catholic Rome, everyone can agree that de Dominis was a spineless heretic loyal only to the hand feeding him. I’m sure it doesn’t matter that this was the mind behind a vision of Christian unity touted by millions.

The idea of individual parishes having to figure this out is itself a great argument for the Magisterium.

Though, in fairness, I think his ultimate conclusion sounds a bit like he took the long way to Aristotle and Aquinas’ picture, so maybe his statement that God “is timeless without creation and temporal subsequent to creation” is not as radical as it first looks. If I elaborate, though, this footnote will become an invasive species, multiplying until it chokes out everything else.

Inferno, Canto II. Compare with this chilling passage from C.S. Lewis’ The Screwtape Letters:

“…the safest road to Hell is the gradual one — the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts.”

Hell, of course, is the only party helped by keeping the road unmarked.

Earlier, I quoted a passage from the Great High Priestly Prayer. Note this particular line:

I pray also for those who will believe in me through their message, that all of them may be one

Through their message. No one comes to the Father except through Christ, and here Christ expects the world to come to know Him through His apostles. It’s difficult to imagine how Christ could have more closely linked following Him with following His disciples.

As far as I can see, it would be consistent for someone following the de Dominis paradigm to say that those who never hear the Gospel can be saved by perhaps being given a post-mortem chance to assent to the “essentials.” So although the de Dominis paradigm doesn’t mean that those who never heard the Gospel are automatically damned, the definition paradigm can incorporate them much more naturally, as we shall see.

Catholics and Orthodox. Protestants actually have less of the Bible than the Arians did.

This, by the way, is part of what is meant by the formula extra ecclesiam nulla salus, “outside of the Church there is no salvation.” That is to say, “All you German princes who are seizing the Reformation as an opportunity to buck Rome’s spiritual sovereignty, listen up: You know very well that Peter has the authority to bind and loose. You put your salvation on the line by rejecting him.” It is not aimed at those born into Protestantism five hundred years later. This is what the Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches (See especially Paragraph 217).

I know it’s a bit derivative, but there is nothing more Catholic than baptizing the good in something and scrapping the rest. We are an omnivorous religion with a stomach of absolute steel.

It is the general practice of the Catholic Church to accept Protestant Baptisms so long as they observe the proper matter and form.

The Eastern Orthodox, I think, operate on a third paradigm. We could call it the “completion paradigm.” Like the essentials paradigm, it believes there are no further bays or inlets to measure along the coastline. Like the definition paradigm, it believes that the teaching of the Bible became clearer through centuries of Church Councils and deliberation. Unlike either paradigm, however, it claims to be complete. By contrast, the essentials paradigm claims incompleteness and disbelieves in anything firm beyond what it has, and the definition paradigm believes it has the complete truth but that more within that truth will continue to be unpacked over time.

Presbyterian here.

Two things.

First, the Reformation isn't the cause of all the ills of which you complain. It's the result of the failure of the Vatican project by the end of the fifteenth century. Pretending that didn't happen

Second, the whole bit about an infallible authority sounds great, in theory. It would certainly solve a lot of problems. Of course, the very fact that we're having this conversation suggests that, in practice, things have not worked out that way. C.f. the aforementioned collapse of the Vatican project. The Eastern church never bought Rome's claims to supremacy. Hence AD 1054. But once the Avignon Papacy happened, the bloom was entirely off that rose.

That's the thing about supposedly infallible authority figures/structures. They can't afford to ever be wrong. Not even once. As soon as you've got more than one dude claiming to be the heir of St. Peter, the jig is up. Entirely. The whole premise of the project is that Rome can always be trusted. At every point in time. But it quite obviously cannot.

And sticking your fingers in your ears and pretending none of those things happened, or that an unknown but likely quite large portion of the hierarchy belong to the Pink Mafia, isn't a good faith basis for discussion.