This is the first of a new section of Reformation Catholicism titled ‘The Guide,” which will give concrete guidance to those interested in making a serious effort to discover whether the Catholic Church is who she claims to be. You can visit the new page here.

The central claim of Catholicism is this: The Triune God created us for a loving relationship with Himself, and although we are in rebellion against Him, He came to heal us by becoming human, living among us, dying at our hands, and rising again. Now, by joining ourselves to His Body, the Church, we can be restored and sent out to proclaim the Good News of man’s reconciliation with his God.

This should all be pretty familiar to the Protestant audience I write for. What is less familiar is everything the Catholic Church teaches is contained within it. If the picture is so simple, where did all this stuff come from? We leave the Church in the Acts of the Apostles living out a kind of communitarian arrangement, with her leaders roaming around planting new parishes and trying not to get killed. How did she get from there to a global system of priests and bishops, from spontaneous proclamations of the Gospel to dozens of memorized prayers, from preaching about Christ to setting out moral teachings on birth control, euthanasia, and more? And when did she get so wealthy?

All fair questions, though I would object to some of their premises. The point is, when making substantial contact with Catholicism for the first time, many Protestants find it all utterly baffling. Arcane, elaborate, and apparently pointless. It instantly calls to mind what Jesus says to the Pharisees:

Thus you [Pharisees] nullify the word of God by your tradition that you have handed down.1

Remember, though, that Our Lord also says:

The teachers of the law and the Pharisees sit in Moses’ seat [Greek cathedra]. So you must be careful to do everything they tell you.

The question is not whether the Catholic Church today is identical in all respects to the Church of 33 AD, any more than Jesus was concerned to show that the practice and teaching of the Pharisees were exactly those of Moses. Instead, the question is whether the Catholic Church has inherited the authority to speak definitively about what the Gospel reveals. That’s the big-picture question—let’s start with something more modest (and more pressing): How would you even begin finding something like that out? What follows are some principles and tips for those trying to understand Catholicism.

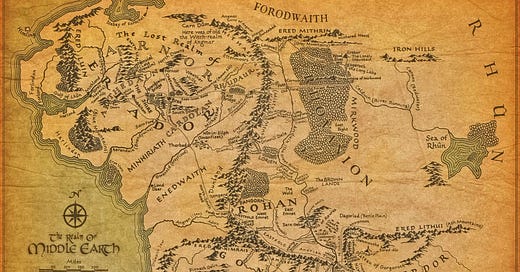

When I explore new topics, I think of the subject as a blank map, which reading, listening, and conversing slowly fill in, first with the most prominent landmarks, then later with details about all the trails and streams. Here are some of the first features you should add to your Catholicism map:

The Church

The claim is not that the Roman Church simply has the highest percentage of correct teachings, or that she is simply the biggest and best of all denominations. Rather, it is that Jesus has given us His promise that her teaching will never err in matters of faith and morals. Church leadership can be understood in three broad tiers: First, local priests (Greek presbuteroi) look after individual churches or “parishes.” Their function is to guide their flocks, teach them the Faith, and administer the Sacraments. Second, bishops (Greek episcopai) look after the parishes within a geographical territory called a diocese. They are primarily teachers, a sort of local doctrinal magistrate, but they also oversee the various administrative and disciplinary tasks of the diocese. Third, the Pope is the bishop of Rome, which is important because that is the seat (Greek cathedra) of St. Peter, to whom Christ entrusted the Keys of the Kingdom. The Pope is not a C.E.O. or a king, but a global head pastor and final court of appeals on matters of faith and morals. He is the shepherd of all Christians, whether they recognize his authority or not, and it is his task to guide the Church through the turbulent cultural and political waters the Church constantly finds herself in during her earthly pilgrimage.

The Sacraments

The seven Sacraments are means instituted by Christ for Christians to become “partakers of the divine nature.” Akin to how the sacrificial system of the Old Testament provided objective ways to make freewill offerings to God, seek forgiveness, and more, the Sacraments are objective ways for Christians to sanctify their lives and mark them as dedicated to Christ, both by outward signs and the inward changes they effect. It would be too involved a task to take up even an brief summary of each here, but you should think of the Sacraments as the chief equipment, training, and diet we need to make it up the mountain to our home. Because their power is simply the power of Christ, this helps remind us that we contribute nothing to our homeward journey that doesn’t come from God in the first place.

The “Stuff”

When you first hear Catholics talk about the spiritual life, you will likely be struck by the sheer variety and strangeness of it. If you, like me, encountered the fantasy genre long before Catholicism, it might seem that “Supreme Pontifex,” “charisms,” “the Liturgy of the Eucharist,” “mystical visions,” “the Magisterium,” and “thuribles” all sit more comfortably next to “elves and dwarves” than “taxes and ties.” And if you, also like me, were raised Evangelical, your instinctual reaction to all this will be to recoil, as the question “What could all this possibly have to do with Jesus?” leaps to mind with sirens and flashing lights. Permit me to counsel patience. It really is like learning a new language. You may not presently even have the conceptual scaffolding to make sense of the intercession of the saints, much less the “luminous darkness.” Take it one step at a time, and feel free to simply ignore anything that isn’t helpful for the time being. I myself did not warm up to Marian piety for almost a year after I became Catholic. I promise that if you take your initial reaction not rhetorically but as a serious line of inquiry, you will find that every Catholic practice is radically Christocentric, though it may not be obvious to the mistrustful or untrained eye.

This first sketch of the Catholic Church, of course, does not represent what are necessarily the most important Catholic doctrines. This is an introduction with a specific audience in mind, not a systematic theology. The Trinity, the Incarnation, the Atonement and Resurrection, the Bible—all these would feature prominently in a work like that. But because Protestants and Catholics are generally on the same page about these matters, I have passed over them for the time being.

So you’re ready to depart, map and pencil in hand; where to next? Obviously, I will keep writing here, but there are many other great resources. And many bad ones! I keep a running list of the good ones here. Anything outside of these are worth taking with a grain, bucket, or barge of salt. If you find yourself on Catholic Twitter, Instagram, or Facebook, you’ve taken a wrong turn. If you stumble on anything talking about “trads,” just go ahead and close the tab for now.2 Focus on prayer, careful study, and attentively listening to what the Spirit might be saying to you. It has never been easier to study these matters, both because of the quantity and availability of excellent resources, and because since Vatican II the Catholic Church has endeavored to use language less opaque to nonCatholic Christians, our “separated brethren.”

Turning to practical recommendations, look at the Mass times for your local parish. They will have several on Sunday and probably some on Saturday night, so you won’t have to skip your church’s Sunday morning service. When you visit, find out (the priest will know) when they are running OCIA (Order of Catholic Initiation for Adults) and check that out. Even if you’re not intending to become Catholic, these classes are designed to walk you through the basics. They will also put you in touch with other people asking questions, and (ideally) a competent priest or layperson capable of answering them. If you look around and can’t find a good dialogue partner/theological guide, please reach out and let me know—I keep up several correspondences and would be happy to talk!

It will also be helpful to ask your Protestant pastors and friends why they’re not Catholic. You will quickly discover almost all of them either haven’t thought much about it or believe common misconceptions (Catholics worship Mary, believe in works-based salvation, etc.). During this process, record your questions, either on paper or in your Notes app. Start by asking yourself this: “What would it take for me to be convinced Catholicism was true?” List as many objections that would need to be answered, claims that would need to be defended, etc., as possible. It would be great to add anything new your Protestant conversation partners bring up. When you ascertain the Catholic response, jot it down. If it puts your initial question to rest, mark it as closed. If it raises new questions or objections, indicate that your original question is closed and then list the new ones. Why all this record-keeping? It’s biblical. Over and over, the Israelites are entreated to remember. Remember that you were slaves, remember that the Lord brought you from Egypt, remember that He drove out the nations before you, remember the Covenant. We are prone to forget what is not right in front of us. Satan, of course, does not want you to give sustained attention to your questions. Do not let “the worries of this life, the deceitfulness of wealth and the desires for other things come in and choke the word, making it unfruitful;” Remember.

Lastly, follow your interest. The questions and subjects you are most drawn to are the best ones to start with.

That’s enough to get you started. I leave you with the words of Pope St. John Paul II:

Do not be afraid. Open wide the doors for Christ!

When this verse is used against Catholics, it is badly wrenched out of context. Jesus is rebuking the Pharisees for using donations to the temple to avoid meeting their responsibility to care for their parents. He’s not rebuking them for using their teaching authority, but rather for using it poorly, in a way that allows them to skirt the law. We might make a distant analogy to politicians in the modern day. You can excoriate them for passing policies that favor their private interests without A) disputing their authority to pass laws, much less B) rejecting laws in general.

There are a lot of people with opinions out there. The Church has a delightful array of people convinced that some fellow Catholics are catastrophically mistaken on some point. There will be time enough to wade into the nitty-gritty of intra-Catholic disputes. In the meantime, don’t be too bothered by Catholics arguing with each other—this is simply part of how doctrine gets hammered out. The truly miraculous thing is that although it may (on very rare occasions) come to blows, every Catholic comes around the same Communion table every Sunday, amidst disagreements that would have divided Protestants several times over.