My first reaction to the intercession of the saints was a kind of terrified grief at the idea of someone butting in between God and me, like finding the door to your home replaced by bullet-proof glass: alarming, bewildering, and certainly not an upgrade. I have given thought to the theological roots of this attitude, and I sought to capture one factor in my post on analogical predication. Here, though, I’m less interested in excavating ideas than offering a distinction to help clarify them.

Catholic theology is always talking about “mediation.” The Sacraments mediate grace, Mary mediates Christ, the saints mediate whatever they patronize, and so on. But this “mediation,” is frequently the locus of pernicious misunderstanding. What we need is a distinction between “mediation” and “intermediation.” And there is no better day than today, Christmas, to draw one.

Let’s take water as our key metaphor. Mediation is the relationship between rivers and lakes. Rivers mediate water to a lake. In a sense, rivers just are the water, so if a river is moving in the right direction, it couldn’t but add to the lake’s store. Notice, though, that rivers are not the only way water gets into lakes. There are also springs and rains, and perhaps other things geologists keep secret from me. Notice further that none of these modes are competitive. Being fed from an aquifer does not, indeed cannot, stop rivers and rains from filling up a lake. Rivers aren’t even mutually exclusive with other rivers—the more the merrier!

Contrast with intermediation, embodied not by rivers but locks. Locks stand between two bodies of water, bodies which rest at different heights or for some other reason can’t be allowed unregulated flow. They hold the two apart, so that any interaction they do have will take place in the lock itself, which will always be closed to at least one side. Locks do not multiply but control water’s flow.

Yet we needn’t reach for aquatic imagery. This is simply what the words mean. When people have a mediated conversation, they both sit down, face to face, with a third person in the room to help them communicate better with one another. The mediator is there to increase the “surface area” of their contact. The more she succeeds, the more the people understand one another, and the less they depend on her. An intermediary works instead as a go-between, serving as a third, ostensibly neutral agent intended to minimize contact. Intermediaries stand between, mediators stand alongside.

The trouble, of course, is that until you’ve grasped the difference, it will seem that Catholics are always sliding from talking about the saints (and angels, and the greatest saint, Mary) as mediators one moment to intermediaries the next. This is for the same reason that to both polytheists and non-trinitarian monotheists, Christians seem to swing between wildly inconsistent poles when they talk about believing in “One God, the Father Almighty…and His Son, Jesus Christ, Our Lord.” Just as Christians who have the basic concept of the Trinity in their blood and marrow don’t usually jump the linguistic hurdles at every point to keep their Trinitarian language perfectly disciplined, so Catholics who instinctively (or even explicitly) understand the difference between mediation and intermediation may not rigorously demand every word be regulated to satisfy onlookers. Indeed, it is a mark of Christian freedom that the concept goes deep enough that they don’t have to scrupulously monitor it. It’s the same type of freedom Christendom found when she so deeply shook off the burdens of her pagan ancestors that the gods, defanged, could safely be introduced into literature and poetry. Consider the opening of Dante’s Paradiso,1 in which Dante imagines himself brought into the deepest joys of Christian heaven:

Gracious Apollo! in this crowing test Make me the conduit that thy power runs through!

Has Dante, against all odds, slipped into a moment of shameful paganism right in the heart of God’s power? No. No such man could write what appears later in the same canto (chapter):

Then she began: “All beings great and small Are linked in order; and this orderliness Is form, which stamps God’s likeness on the All.

Dante can express deepest conviction in God’s sovereign rule over all things, that they all lean toward Him as their final end and find the very orderliness of their being in God’s own “stamp,” right alongside his invocation of Apollo for help. Again, to the uninitiated, this might seem a tangle of contradiction, theological backsliding. But it is not so. To the completed Christian, the good of creatures can be given its full due without threatening God. And the gods of Greece and Rome are so thoroughly defeated that they may even be baptized and turned to the service of the One True God.

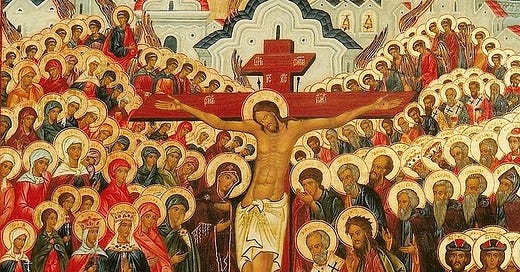

The saints, then, are mediators. Unlike water in a river, they retain their individuality. Unlike legal mediators, they are not mere tools. Unlike Apollo,2 they are fellow humans. Yet they are humans plunged into the depths of the divine fire, made so to shine that one cannot enjoy their friendship without starting to glow a bit. The saints do not block our access to God’s love, but open more and more channels, digging new ditches for new streams of love in our hearts. Granted, Catholics may use the language of intermediation at times; we’re reaching for words to express grace, the inexpressible. We take similar poetic license when describing the Trinity as a family, or “divine dance,” or clover. But deep in the Catholic conception of the saints is an unshakable confidence that God wishes to fill us with Himself so thoroughly that we cannot but overflow, cannot but turn around and offer our prayers and friendship to our fellow Christians. You, too, are called to this high calling, to become a saint. Thus Saint Paul:

And we all, who with unveiled faces contemplate the Lord’s glory, are being transformed into his image with ever-increasing glory, which comes from the Lord, who is the Spirit.

I am, of course, not the first convert to encounter and overcome this fear. On this Christmas Day, I leave you with the words of St. John Henry Newman, who with St. Melchizedek ought to be the patron of Protestant converts. He says that despite what he initially thought,

there was no cloud interposed between the creature and the Object of his faith and love. The command practically enforced was, "My son, give Me thy heart." The devotions then to Angels and Saints as little interfered with the incommunicable glory of the Eternal, as the love which we bear our friends and relations, our tender human sympathies, are inconsistent with that supreme homage of the heart to the Unseen, which really does but sanctify and exalt, not jealously destroy, what is of earth.3

< Previous Saints FAQ | Back to FAQ List | Next Saints FAQ >

I’m citing the Dorothy Sayers translation.

Probably, for Dante, to be understood as something like an angel. For the Greek gods transposed into angels within the Christian system, see C.S. Lewis, The Discarded Image for a scholarly treatment, or his Perelandra and That Hideous Strength to see it play out in fiction.

John Henry Newman was an Anglican priest and scholar at Oxford in the 1800’s who was forced to give up his post when he decided to become Catholic. This quote is from Apologia Pro Vita Sua, the autobiographical record of how he came to believe in the Catholic faith. The full text is available online here. I’m quoting from p. 196.