As of writing, there are a whopping 43 movies and TV series in the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU), produced over 17 years. Almost 800 named characters have appeared on screen, each with their own personality, motivation, and relationships with other characters. Managing all this in concert with the steadily expanded lore easily adds up to a full-time job. In fact, it is a full-time job: Marvel Studios has an employee entirely dedicated to maintaining continuity across its sprawling timeline. Now, our unmitigated obsession with hyper-realistic details is interesting in itself, as if what we really wanted from block-buster fantasy movies was new material for engineers to analyze. But I am interested in a more concrete line of argument.

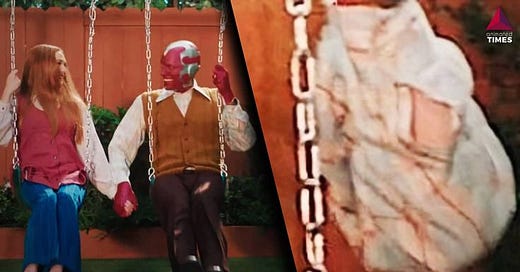

Despite the undivided focus of someone made in the image of God, Marvel still suffers from substantial errors.1 This extends beyond storytelling and world-building—the multi-billion dollar operation has let other blunders slip past unnoticed. Unnoticed by the studio, at least. The internet always notices, and gleefully points it out. Such was the case with this promo shot from WandaVision:

This show had a budget of roughly 25 million dollars. Per episode.

Even so, Marvel Studios represents the best-case scenario for the internal consistency of human creative projects. It has everything going for it: a “Parliament” overseeing the production of every movie and TV show, a dedicated continuity manager, a budget larger than the GDP of some countries, a shared vision, and a profit incentive to make sure each story lines up. They haven’t had to endure the instability of leadership change even once. If a situation could be more conducive to internal coherence, it's hard to see how. And they still fail.2

The Catholic Church does not enjoy these ideal conditions. There have been 266 popes, hailing from divergent theological schools, different modes of life (humble monks to the sons of rich and powerful bankers), different languages, different scientific outlooks, and different personal priorities. They have been scoundrels as well as saints. Some privately taught error or held heretical views before their election. And whereas Marvel has only had to keep things together for a scant 17 years, the Church is on her 1991st.

It’s hard to properly articulate how astounding it is that the Church’s doctrine has remained completely self-consistent the entire time, with no exceptions.

When I first began investigating Catholicism, I thought it would be open and shut. Because the Chuch claims infallibility, if you can get even one clear-cut case of self-contradiction, that would be enough to topple the whole thing. Anyone who has spent time with the Enchiridion Symbolorum, a compilation of the sources of Catholic dogma, will already know that by all human measures, constructing an elaborate systematic theology with perfect internal coherence on this scale is simply impossible. At just over 276,000 words, we see an institution not content to merely repeat the contents of the Apostle’s Creed, or stick to a narrow band of “essentials.” Instead, the Church talks exactly as if she were infallible, fearlessly exercising her authority to condemn some positions and approve others. And this, despite the handful of popes who were too busy sinning to read all the material they were accountable to. How has the Church managed to maintain perfect clarity a hundred times longer than the MCU has even existed?

One possible response is that she hasn’t. Indeed, a simple Google search will bring up a host of blogs and other sources aiming to show just this. Yet a little digging reveals that these attempts suffer the same defect. I’ve chosen the first decent post that popped up when I searched “Times the Catholic Church has contradicted itself” as an illustration. The post is here, and in many ways it’s an excellent article—lots of primary sources, clear argumentation, and plenty of intellectual charity. But scroll down to the comment by Prasanth. The commenter introduces a few primary source passages conveniently overlooked by the original post, and offers a poignant diagnosis:

Look friend, when you argue on how the Church teaches X here and says Y there- and it’s a ‘contradiction’, then it’s no better than a really foolish Atheist saying that the Bible saying “You shall not Kill” in the Ten Commandments, and then goes on listing a whole range of places where one is not simply allowed, but commanded to kill, and all the places where Death Penalty is mandated in the Mosaic Law.”

“Look friend” is such a funny way to start this paragraph.

The poster’s reply makes a subtle but important move. Once he’s done logic-choping the 10 Commandments example, he completely compromises the argument presented in the main article by retreating from his thesis.

Prasanth uses “X” and “Y” to represent two statements in the Bible that stand in apparent contradiction. Think of them as oil and water—mutually exclusive by nature. At least, if you don’t have an emulsifier. In the Bible, whenever X and Y seem to contradict one another, you should always look for Z, the idea that unites and synthesizes them into a whole. In this case, invincible ignorance is the concept needed to resolve the apparent contradiction urged in the post. And the poster’s reply furnishes proof that Prasanth has hit on the right strategy. Instead of arguing that invincible ignorance doesn’t resolve the contradiction, the poster says that invincible ignorance is unbiblical. But notice what that means: the big, scary claim that we started with, “The Catholic Church Has Contradicted Itself And I Can Prove It,” reduces to “This concept from Catholic theology is unbiblical.” The second claim matters, to be sure, but retreating to it implicitly admits that if invincible ignorance were real, the apparent contradiction would vanish. And that’s just to say that they’re not in contradiction at all, since true contradictions are by nature irreconcilable (this is called the “Law of Noncontradiction” and it’s the fundamental law of logic).3

When more serious thinkers take this angle, they have to go deep for material. I remember listening to hours of Protestant v. Catholic debates about whether a particular pope endorsed a heretic in an obscure encyclical (which was debatably just a private letter anyway) and, if so, whether that is the same as endorsing a heresy. At some point, it struck me how absurd the Protestant apologist’s position was. His argument relied on a wide-reaching definition of the Church’s infallibility, since encyclicals are usually regarded as authoritative, but not necessarily infallible.4 Yet even granting this very expansive understanding of the Church’s infallibility (more expansive than the Church herself claims) he still had to go back more than 1500 years to find a plausible candidate for evidence that the Magisterium, the teaching office of the Church, had contradicted itself. To adapt a phrase from St. Edith Stein, “Only the person blinded by the passion of controversy could deny” that the very premise of the debate is a decent argument for Catholicism.

Say you grant my argument, at least in outline. You might still disagree about its import. After all, mere coherence isn’t the same as being right (despite what certain epistemologists say). There might be all kinds of explanations for how the Church has managed to preserve an internally consistent set of doctrines across two millenia. Perhaps she just doesn’t say that much. After all, if we limit our view to statements pronounced ex cathedra, that is, solemnly declared dogma of the Church in the most formal way possible, there are only two. If this were the whole picture, the Church would have far less to keep track of than Marvel! But it is not the whole picture. For starters, the ex cathedra pronouncement is only a formalized version of something that has been around since St. Peter, the ability of the pope to definitively settle theological disputes. Past popes might not have used the formula we’ve since designated for such purposes, but they could and did say things like, “Many people have said X, and others Y, but I now declare that Y is true and X is false.” Earlier I mentioned the Encyridion Symbolorum. Again, this book is more than a quarter-million words long. There have been plenty of chances for us to blow it both publicly and permanently.

When I pitched a version of this argument to an extensively-published philosopher of religion, he said something along these lines: “If these instances are all independent, that’s very impressive. But I just don’t know the history well enough to evaluate it.” In other words, if, as I say, the men who have occupied the Chair of St. Peter come from such disparate circumstances, it is fair to conclude that their mutual theological coherence can be best explained by divine intervention. But the comparison with Marvel Studios shows that this philosopher was too optimistic about human abilities. Even if all the popes were determined to study all previous declarations and quadruple-check for errors before declaring anything (and they weren’t), contradictions would still crop up across 2000 years. A team of people with shared motivations, culture, language, scientific outlook, and a full-time continuity manager can’t even keep it up for 17 years—despite the fact that, compared with the complexity of Catholic theology, Marvel Studios writes nursery tales. This philosopher was also being too modest about his historical abilities. All he needs to do is look at what arguments people go for when trying to dispute the Church’s claim to infallibility, and that will be enough to illustrate the weakness of the objections.

Let me boil it all down to this:

Jesus promised to send His Spirit, who would “lead you (plural) into all truth.”

True statements never contradict one another.

Given enough time and development, all merely human systems produce self-contradictions.

Catholic teaching is a system with time and development that has not contradicted itself.

Catholic teaching must not be a merely human system.

Therefore, Jesus’ promise must have been given to the Catholic Church.

This post has been a defense of (3), and an indirect argument for (4). Anyone can see that by all human measures, Marvel ought to be better off here than the Catholic Church. The fact that it’s not is one more reason to suspect the waters of the Tiber aren’t quite as muddy as some would have us believe.5

< Previous Argument | Back to the Unorganized List | F.A.Q.’s >

Please enjoy this mercilessly compiled Buzzfeed article.

They’re not the only ones. tvtropes.org has a “headscratchers” page for basically every work of fiction that exists. So don’t be too hard on Marvel. After all, it wasn’t long ago that Star Wars was attacked for showing bombs falling out of a ship in space, and then exploding into flames on impact… in space.

I am not saying this is the best possible reply to the original argument. In fact a better one comes a few comments down from “Francisco Mahusay.” But the author doesn’t respond to this second comment, perhaps because he can’t.

Getting a handle on the shades of authority of different pronouncements and documents from the Church takes practice. The very first section of Ludwig Ott’s The Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma has an excellent treatment of this, but is far from approachable for beginners.

Having actually seen the Tiber in person, I have to admit that it’s somewhat beyond muddy. Fortunately, my faith is in the Spirit’s guidance of the Church and not in the sanitation abilities of the Italian government. Fortunate indeed.