Veneration III: The "But you're LITERALLY bowing to an image!!!!" Objection

Veneration III--A Frequently Argued Quandary

To worship something is to make it your final end, your telos. And as St. Thomas Aquinas reminds us, “the divine goodness is the end of all things.”1 Therefore, to make anything besides God your final end is to lie about your very nature. This is why idolatry, the worship of anything besides God, is such a severe sin. Yet Protestants frequently accuse Catholics (and Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox) of just this crime, alleging that our statues and icons are the “graven images” banned in the First Commandment—and it’s not hard to see why. We frequently pray, bow, or light candles before them. The Eastern Orthodox kiss them, like, a lot. I admit that to the uninitiated (to say nothing of the suspicious and hostile) it certainly looks like idol worship. As might be expected, Lewis puts it best in the introduction to Mere Christianity, where he explains why the Blessed Virgin Mary will not appear in the book (and what holds for the Theotokos holds for all veneration):

…the opposed Protestant beliefs on this subject call forth feelings which go down to the very roots of all Monotheism whatever. To radical Protestants it seems that the distinction between Creator and creature (however holy) is imperilled: that Polytheism is risen again.2

Lewis’ characteristically effortless prose conceals exact precision. He is right to describe the Protestant reaction as involving both belief, which tracks reason, and feeling, a kind of aesthetic and even moral disgust. It’s an instance of what I call the “Cathol-ick.” I’ll set that aside for the moment, though in reality it plays just as important a role in the reaction against veneration as any syllogism. Here, I treat the belief side—the side directly responsive to reason.

The question is whether anything separates two supposedly distinct actions (veneration and worship). We must begin, then, by thinking about the nature of action.3

Actions are always done for reasons. They aim at bringing things about. Because of this, actions are inherently intelligible; the aim of an action is built into it, so to speak. You can read the intention in the action itself. When you furtively bury Fireball airplane shooters beneath a mound of popcorn in the movie theater lobby, anyone watching will clearly understand what you’re up to: you’re hiding alcohol. Furthermore, several actions (and therefore several intentions) can be nested together. So you have a larger project, Sneaking alcohol into the movies, composed of several smaller actions, each designated by a specific intention and each directed toward the larger project. So you will bring the Fireball, then buy popcorn, then hide the alcohol, then bootleg it in. In any action with a structure like this, you have the intention of the specific action in question as well as a motivation, the larger project it’s part of. So you intend to sneak in the alcohol (including all the sub-actions that entails), and your motivation is to survive the latest in the relentless onslaught of Marvel movies you only keep watching because of a decade of sunk costs.

For an action to be morally acceptable, neither the intention nor the motivation may be tainted with evil. You may neither intend intrinsically evil actions (i.e., dismembering an unborn infant) nor undertake morally neutral actions for evil motivations (i.e., using social media as a way to avoid the painful spiritual work of reckoning with God’s call on your life). To be clear, the ends do not justify the means; you may not will an intrinsically evil action even if the motivation is good and it seems like your hand has been forced by necessity. You may not, for example, drop an atomic bomb on thousands of civilians (including two-thirds of Japan’s Catholics), even to avoid what would otherwise have been a gruesome land invasion. Elizabeth Anscombe says it with the appropriate implacability: “Whatever human hopes for the happiness of mankind may be, the only way to that happiness is the observance of God’s law without any deviation.”4 Because the intention of an action is built into the action itself, there is no room for saying, “Well yes, I did scan a Nintendo Switch as a banana in self-checkout, but I intended to pay for it!” Clearly you did not.

The trouble with this straightforward picture is that it can be very difficult to determine the intention (much less the motivation) of an action from the outside. Like a passage of difficult prose, you may need more context than you have to determine its meaning, although the meaning is no less fixed. To the untrained eye, a gardener may seem to be destroying a fruit tree when he is only pruning it. To make matters more confusing, the range of possible intentions far outstrips the range of human expressions. C.S. Lewis notices this, commenting on how strange it is that speaking in tongues (or glossolalia) should be outwardly identical to spewing gibberish:

It looks, therefore, as if we shall have to say that the very same phenomenon which is sometimes not only natural but even pathological is at other times (or at least at one other time) the organ of the Holy Ghost.5

It’s a bit like how you sometimes have to look very carefully before you can tell whether someone is crying or laughing, and then, if they’re crying, you may have to use context to infer whether it’s from joy or grief. Notice: two emotions, exactly opposite, share the same physical expression. Discerning intention sometimes requires more information than the outward act itself offers. Motivation can be even harder—a broader sense of an individual’s goals and self-understanding is often essential.

Catholics can be accused of idol worship along two possible lines. First, the Catholic use of images could be wrongly motivated. That is, whatever the status of “bowing in front of an image,” Catholics are engaged in a sustained effort to displace the Creator with creatures. This seems implausible to me, given what I’ve argued here. But you don’t have to take my word for it. Here’s a passage from Ludwig Ott’s Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma, a book that systematically reports the Church’s teaching without additional theologizing:

The Old Testament prohibition of the making and veneration of images (Ex. 20:4ff) on which the opponents of the veneration of images rely, was intended to prevent the Israelites from relapsing into the idolatry of their pagan environment. The prohibition is valid for Christianity only in so far as it prohibits the idolatrous worship of images. Further, even the Old Testament knew exceptions from the prohibition of the making of images: Ex. 25:18 (two cherubim of gold on the ark); Numbers 21:8 (the brazen serpent). Owing to the influence of the Old Testament prohibition of images, Christian veneration of images developed only after the victory of the Church over paganism.6

You don’t have to take Ott’s word either; here’s the Catechism (quoting a combination of St. Basil, Trent, and Vatican II, then St. Thomas Aquinas at the end):

The Christian veneration of images is not contrary to the first commandment which proscribes idols. Indeed, "the honor rendered to an image passes to its prototype," and "whoever venerates an image venerates the person portrayed in it." The honor paid to sacred images is a "respectful veneration," not the adoration due to God alone: “Religious worship is not directed to images in themselves, considered as mere things, but under their distinctive aspect as images leading us on to God incarnate. The movement toward the image does not terminate in it as image, but tends toward that whose image it is.”

A large-scale motivation to worship idols is out. The second line of attack accuses Catholics of directing actions to images that intrinsically intend worship and, if directed towards a physical object, automatically express an intention to worship that object. This argument is much more interesting. To simplify things, let’s treat bowing before an image as a paradigm case; if bowing before a depiction of Mary, a saint, or even Christ crucified is worshipping that image, then all other image-related devotions are also corrupt. But if it’s vindicated, then image veneration in general is.

The puzzle to solve is whether bowing before an image is ambiguous between several possible intentions or always entails a specific, in this case illicit, intention. Is it like the earlier case of cutting the limbs off a fruit tree (which could equally express an intention to prepare it for removal or to flourish come spring), or is it like torture (which always requires forming an evil intention)? Remember, good motivation alone is not enough to get Catholics off the hook. We must cleave absolutely to God’s law.

The place to start is the Bible. I found this interesting post on Stack Exchange while poking around before writing this article:

Question:

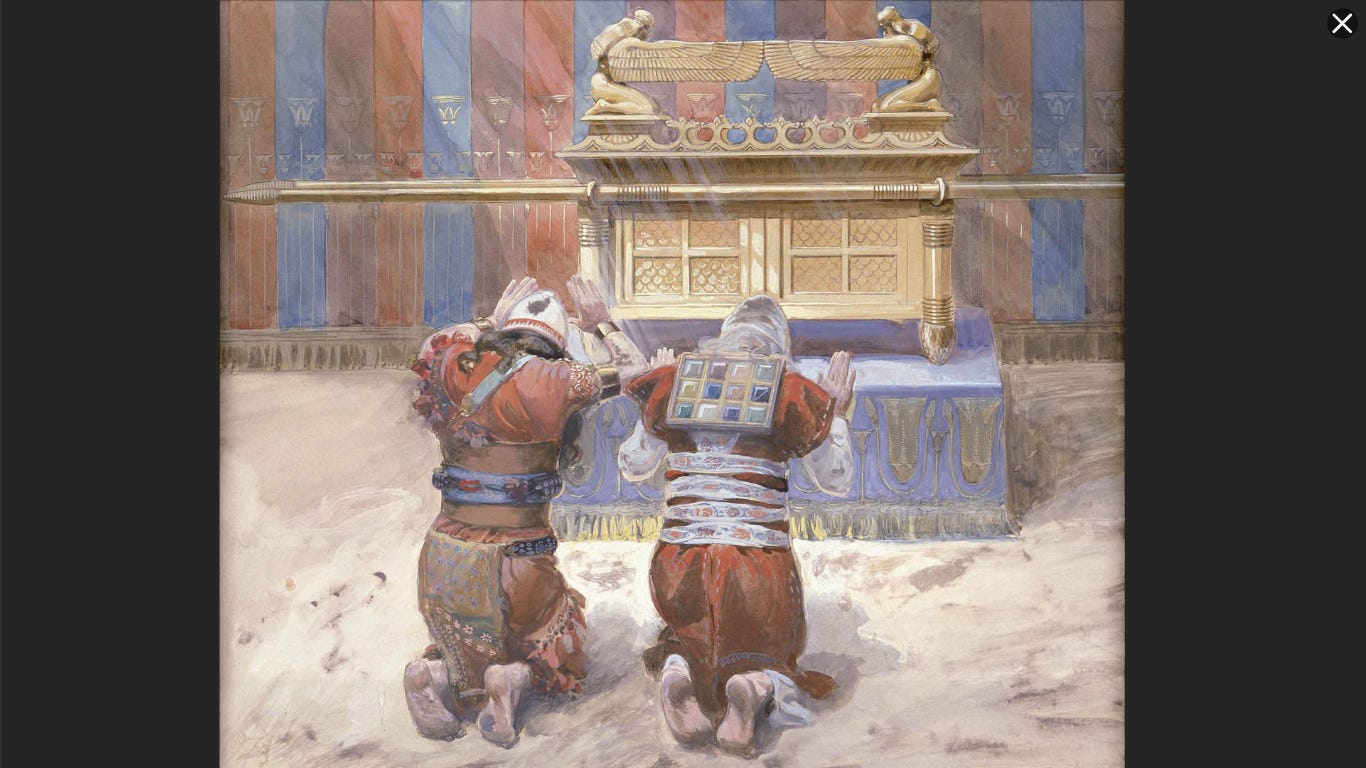

Joshua 7:6

Then Joshua tore his clothes and fell facedown to the ground before the ark of the Lord, remaining there till evening. The elders of Israel did the same, and sprinkled dust on their heads.

Does this break the First Commandment that one is to worship God alone? Why is Joshua permitted to bow down before the Ark?

Answer:

You can show reverence to God's holy ark, and thereby honor God, without considering it God. Is kneeling or bowing to a king necessarily worship? No, nothing in that action assumes they are God, even if you can also do that before God. One distinguishes any action as worship in their heart; the external gestures might look identical. For example, when you ask Jesus for some grace, versus ask your friend to pray for you. The gesture of asking will look the same, but not the inward intention or consideration of who the one being asked is.

Bolding added. The responder’s username is “Sola Gratia;” no Catholic sympathizer, yet I couldn’t ask for a better articulation of the Catholic position. Gratias’s insight is what makes this painting legible:7

But I go further: the act of bowing isn’t intrinsically ordered even to veneration, much less worship. It was a Reformed philosopher who first drew my attention to the import of this passage from 2 Kings 5 (ESV):

Then [Naaman, the healed Syrian] returned to the man of God…And he said, “Behold, I know that there is no God in all the earth but in Israel…from now on your servant will not offer burnt offering or sacrifice to any god but the Lord. In this matter may the Lord pardon your servant: when my master goes into the house of Rimmon to worship there, leaning on my arm, and I bow myself in the house of Rimmon, when I bow myself in the house of Rimmon, the Lord pardon your servant in this matter.” [Elisha] said to him, “Go in peace.”

Naaman is literally bowing before an actual idol, yet Elisha accepts his explanation. Naaman will be bowing as he supports the weight of his elderly master, but won’t be worshipping along with him. This agrees with God’s word to Samuel: “The Lord sees not as man sees: man looks on the outward appearance, but the LORD looks on the heart.” Note well: the action would be intrinsically different if he weren’t physically supporting his master. The point is emphatically not that it’s ok to venerate idols so long as you don’t “intend” it. That would be a contradiction in terms. The point is that “venerate” is not automatically included in “lower yourself to your knees and bend at the waist.”

What this means is that it is impossible to automatically equate bowing before an image with worshipping it. The action is ambiguous between several different intentions. The question, then, is what Catholics do intend when they bow before an image. And to answer that, it is perhaps best to simply ask them. Or their theologians. Or their Catechism. (See above.)

Could it be that Catholics worship images in spite of Catholic teaching, out of deep confusion? This can only be maintained with a strong dose of elitism. It requires the following line of reasoning: “Granted, Eric, when you use images as part of your worship, or you bow before a statue of Mary, or anything else, you understand that you’re really worshipping God and not Mary. But most Catholics don’t get it.” I respond: If millions of Protestants can understand that God alone is God, why couldn’t 1.4 billion Catholics? Recall that every Rosary begins with the Apostle’s Creed, the Sunday Mass includes a group recitation of the Nicene Creed and (as I mentioned in the last post about veneration) features a declaration in the Glory to God that’s as strong as could be asked for:

For You alone are the Holy One,

You alone are the Lord,

You alone are the Most High,

Jesus Christ, with the Holy Spirit,

in the glory of the Father.

In light of all this, you can rest easy when you see things like this:

It works on the exact same principles that explain how worshipping at or even “through” the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem is not the same as praying to it, even if an uninformed first glance seems to say otherwise:

The images that Catholics use are not “graven images” in the biblical sense any more than the angels on the Ark were. We worship neither saint nor stone. Our motivations and intentions are fixed firmly on the Lord. And we hope in faith that through these venerable images, we may join our prayers with those depicted and all the more fervently proclaim with the Mass:

Therefore with angels and archangels,

and with all the company of heaven,

we proclaim your great and glorious name,

forever praising you and saying:

Holy, holy, holy Lord,

God of power and might.

Heaven and earth are full of your glory.

Hosanna in the highest.

< Veneration II: Idolatry Begets Sin | F.A.Q. List | The Church F.A.Q.’s >

Summa Theologiae, Ia, Q44, a4.

We’re on friendly territory, as action theory in its current form developed from the work of Elizabeth Anscombe, one of the greatest minds of the 20th century and a convert to Catholicism. Consider joining me in praying for her canonization.

“The Justice of the Present War Examined.” I couldn’t find it readily available online but I’m happy to send a PDF to anyone who wants it.

Page 342 in the 2023 printing.

It’s housed in The Jewish Museum. Jews (known monotheists) would not very gladly put up a painting of Moses and Joshua worshipping an idol, particularly not one exalting the moment. So Catholics (and Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox) are not the only monotheists who understand this concept.

The Ark is an especially fitting point of reference because there is an ancient tradition of understanding Mary as the New Ark. The prototype, which held the Old Covenant, is surpassed by the antitype, who bore the New Covenant Himself. If Moses and Joshua venerated the first Ark for the sake of the First Covenant, which was powerless to overcome death, how much more should we venerate the New Ark? But I’ll let Catholic Answers do the heavy lifting on this point. I’m grateful once again to

, this time for pointing out that I’d inadvertently set up a neat OT-NT connection here.